Kerim’s Triptych for Sunday, March 24th, 2024

Welcome to Kerim's Triptych, a free newsletter that delivers 3 fabulous links to your email inbox, 3 times a month. If you didn't intend to subscribe, or you don't want to receive these anymore, there is an unsubscribe link at the bottom.

Item 1: Paul Kagame and "the West"

This Bloomberg story about Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, offers an in-depth and nuanced portrait that explains why he is both loved and feared by the international community.

Why he is loved:

Over the decades, Kagame has become possibly the West’s most important African ally. The French owe him for sending troops to save Total’s massive liquefied natural gas project in Mozambique from jihadis; the British last year paid Rwanda £240 million ($304 million) to take in thousands of migrants being held in facilities in the UK (although no one has yet been deported, the affair has ignited a political firestorm for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak); the Americans would like his army to assume a piece of the mercenary business long dominated by Russia’s Wagner Group. Last year, Kagame was named the chair of the Commonwealth of Nations, which is made up mostly of former British colonies, though Rwanda never was one. His former foreign minister is the head of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, the French equivalent.

And why he is feared:

At the same time, Rwanda has become one of the world’s most polarizing nations—viewed from another angle as a Potemkin village led by an authoritarian monster. Kagame has essentially outlawed political opposition, backing his suppression of dissent with what critics including South Africa’s justice ministry, Human Rights Watch and British police say is a global assassination program, which one nongovernmental organization estimates has claimed the lives of hundreds of dissidents. In a 2022 review of Rwanda’s human-rights record, the US State Department cited “credible reports” that Kagame’s regime has carried out “transnational repression against individuals located outside the country, including killings, kidnappings, and violence.” And UN investigators say he has long been party to an intermittent, brutal war in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. Rwanda denies involvement in any assassinations and says it plays no role in the Congo conflict.

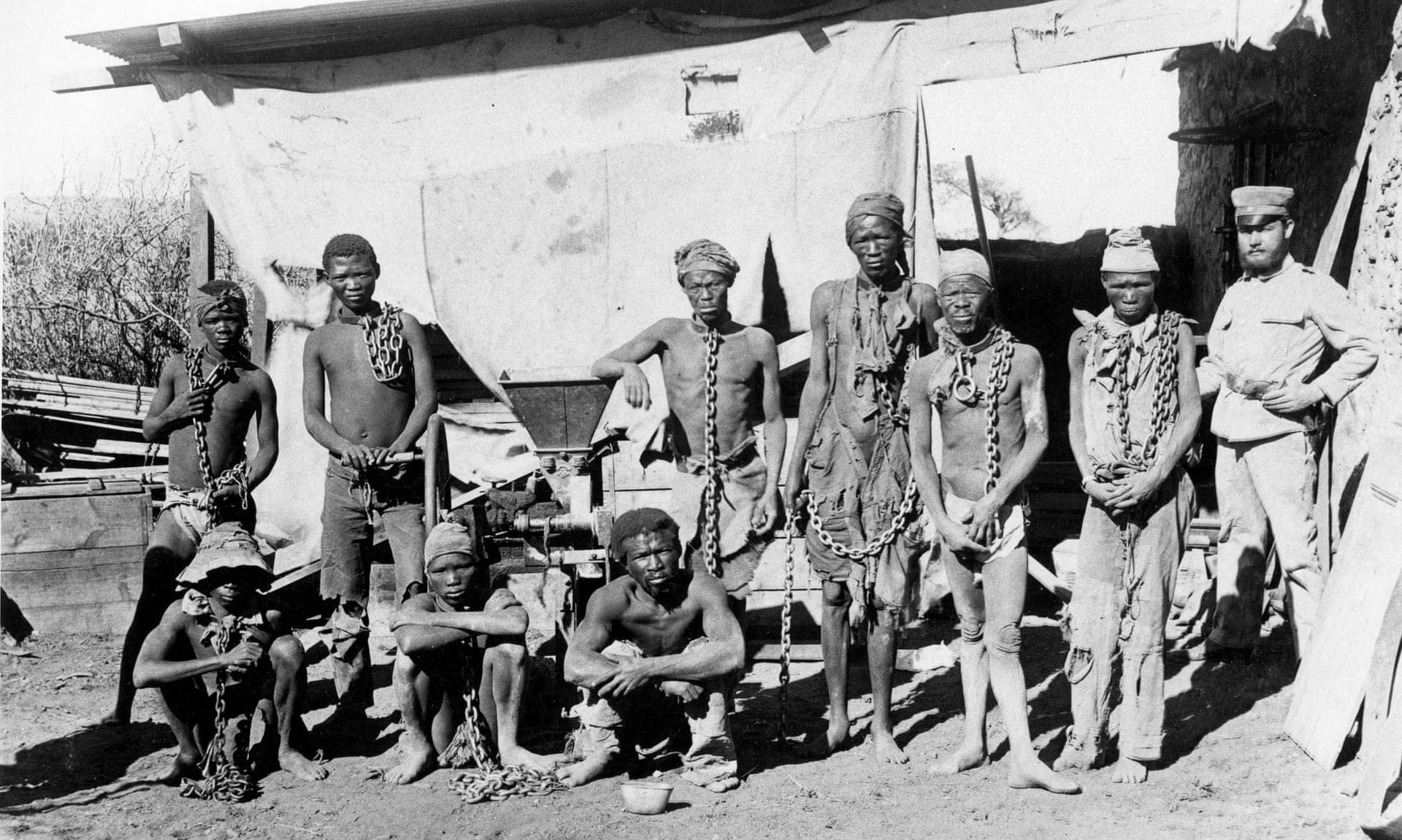

Item 2: German Colonialism

Writing in the New York Review of Books, Thomas Rogers explores why Africans are looking askance at the paltry repatriations they have received from Germany.

He quotes Paul Thomas, a Namibian activist on the topic of the Nama genocide (1904-8):

to this day, we are still landless and in poverty because of what happened 115 years ago. My great-grandfather was beheaded, some of his people were put in concentration camps and worked to death. There is nothing for us in this deal. It is empty.

These debates inevitably bring up German reparations for the Holocaust as a point of comparison and Rogers spends a fair amount of the article deftly exploring debates within German over whether one can even make comparisons between these different genocides.

Item 3: The Battle of Algiers at Fifty

A lovely essay (first published in Film Quarterly in 2017) on the classic 1966 film by Gillo Pontecorvo. Alan O’Leary's article looks at the film through the lens of urban architecture and makes interesting comparisons with contemporary French films like La Haine, calling Battle "the first Banlieue film."

The banlieue film (defined like the western by its geographical location, as Will Higbee points out) typically employs a realist aesthetic that presents the “alienating architecture” of the housing estates to figure the marginalization of its young male protagonists. However, in this cinema, the meaning of the banlieue itself cannot be reduced solely to alienation because it also “remained the only real space of community and belonging.”

O’Leary ends essay with this quote from Gayatri Spivak:

That the “end” of Battle is still a (third) space of possibility that seems to be latent or lost by the time of La Haine confirms the accuracy of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s observation that “the future is always around the corner, there is no victory, but only victories that are also warnings.” That future is named in voiceover to the coda to Battle, which announces that Algerian independence would come two years after the events shown, yet the coda also visually announces the persistence in urban space of Fanon’s colonial world cut in two. In that sense, Battle adumbrates a hauntology of empire in the postcolonial period, a sense of a project still unfinished.

Endnote

Enjoying Triptych? Please consider writing a short blurb/endorsement to help me promote the newsletter. You can just email it to me, or enter it in this Google form.

You can also show your appreciation by switching to a paid account. A big shout out to my current paid subscribers, whose contributions keep this place running. Thank you.

Member discussion